The SpaceNews Awards celebrate excellence and innovation in the global space industry. Past winners include U.S. Space Force Gen. John “Jay” Raymond, SpaceX President and Chief Operating Officer Gwynne Shotwell, ESA Director General Jan Woerner and many more.

The 2020 SpaceNews Awards are given to organizations, programs and people with demonstrable achievements in the space arena during the preceding 12 months.

The 2020 winners are:

♦ Government Mission of the Year ♦

♦ Commercial Mission of the Year ♦

♦ Government Leader of the Year ♦

♦ Large Company of the Year ♦

♦ Small Company of the Year ♦

♦ Large Company Leader of the Year ♦

♦ Small Company Leader of the Year ♦

♦ Startup of the Year ♦

♦ Space Stewardship Award ♦

Government Mission of the Year – MARS 2020

Rarely has a spacecraft had a more appropriate name. In early March, NASA concluded a student competition to name the rover flying on the Mars 2020 mission by announcing the winning name: Perseverance. That name was intended to represent the most important human quality, in the words of the seventh grader who proposed it, and one essential to the exploration of the red planet.

Within weeks, that name took on a new significance as the coronavirus pandemic brought an end to business as usual while technicians were preparing the spacecraft for a July launch. One reason Mars missions are so challenging is the narrow launch windows available to them: if Mars 2020 didn’t launch by mid-August, it would have to wait two years for its next chance. That was the fate for Europe’s ExoMars, which slipped to 2022 when the European Space Agency concluded it could not get the spacecraft ready in time amid the restrictions imposed by the pandemic.

NASA wanted to avoid that two-year delay, which it estimated would cost the agency as much as a half-billion dollars, and thus made the mission one of its highest priorities. It would not be easy, though. “Putting a spacecraft together that’s going to Mars and not making a mistake is hard no matter what,” said Matt Wallace, the deputy project manager for Mars 2020. “Trying to do it during the middle of a pandemic is a lot harder.”

The project took measures to keep workers safe while also keeping the mission on schedule. That included using NASA aircraft, rather than commercial airliners, to fly personnel and equipment to Florida for launch preparations, limiting their exposure to the coronavirus. Late in the launch preparations, they added a small plaque to the rover to honor the healthcare workers on the front lines of the pandemic.

Those efforts paid off with a successful Atlas 5 launch July 30, sending Perseverance on to Mars. If all goes well, Perseverance will land on Mars in February and begin its studies of the planet, including collecting samples of Mars for later return to Earth.

That launch also allowed NASA and ESA to move ahead with their joint Mars Sample Return program, an effort to return the samples cached by Perseverance that involves another lander and an orbiter, one that will take at least a decade to complete. Perseverance — the rover and the human quality — will remain important for years to come.

– back to top –

Commercial Mission of the Year – SPACEX DEMO-2

From the early days of NASA’s commercial cargo program, SpaceX officials would point to one aspect of the design of their Dragon spacecraft that spoke to their future ambitions: a porthole. A cargo spacecraft didn’t need a porthole, since there would be no one inside to look through it. However, SpaceX envisioned a day when Dragon would carry people who would want to look out that window.

That day came on May 30, 2020, when a Crew Dragon spacecraft lifted off atop a Falcon 9 rocket from the Kennedy Space Center on the Demo-2 mission. On board the spacecraft were NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley, who arrived a day later at the International Space Station. After a two-month stay at the ISS, they departed the station and safely splashed down in the Gulf of Mexico Aug. 2.

For NASA, the mission was a relief: after years of delays, it could end its reliance on Russia’s Soyuz to get astronauts to the station. It was also a vindication of NASA’s long-controversial approach of partnering with industry to develop crewed spacecraft, breaking with decades of traditional government contracting and management.

“It’s not an exaggeration to state that, with this milestone, NASA and SpaceX have changed the historical arc of human space transportation,” Phil McAlister, director of commercial spaceflight at NASA Headquarters, said after the agency formally certified Crew Dragon for regular missions to the station in November. “Now, for the first time in history, there is a commercial capability from a private-sector entity to safely and reliably transport people to orbit.”

Those people include more than just astronauts. SpaceX has agreements with Axiom Space and Space Adventures for commercial missions using Crew Dragon, including one for Axiom that will launch in late 2021. Crew Dragon can enable the business plans of companies proposing commercial space stations, supporting NASA’s low Earth orbit commercialization initiative as the agency looks to retire the ISS in a decade.

“Human spaceflight was always the fundamental goal of SpaceX,” Elon Musk, founder and chief executive of the company, said after the Demo-2 launch, emphasizing his desire to make humanity multiplanetary. “I cannot emphasize this enough. This is the thing that we need to do.”

If SpaceX achieves that multiplanetary goal, it will be with other spacecraft, like its Starship under development. But Crew Dragon demonstrated that SpaceX has the ability to safely launch and return people, validating a vision that goes back to a porthole in a cargo spacecraft.

– back to top –

Government Leader of the Year – KATHY LUEDERS

Kathy Lueders thought she was going to the Bahamas. As a co-op student, she was told she had won a trip to “Nassau” and immediately envisioned white sand beaches and blue waters. “I thought I’d won the lottery,” she recalled at a recent conference. It turns out, though, that she had instead won a trip to NASA. (The co-op manager, she explained, had a “very thick southern accent.”)

The real winner of the lottery might have been NASA. That visit changed her life, she said, and she started working at NASA in 1992 on the shuttle and space station programs. In 2013, she became manager of NASA’s commercial crew program at a critical time: the agency was preparing to select the companies that would get billions of dollars to complete development of vehicles to transport astronauts to and from the station.

Lueders ran the program with a steady hand through its up and downs, including setbacks like a thruster test that destroyed a Crew Dragon spacecraft on a test stand and the flawed uncrewed test flight of Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner last December. That approach was vindicated with the successful launch May 30 of SpaceX’s Demo-2 mission with two NASA astronauts on board, who spent two months on the International Space Station before returning safely in early August.

But even before the Crew Dragon splashed down in the Gulf of Mexico, Lueders had moved on. In June, NASA named her the new associate administrator for human exploration and operations, overseeing not just ISS and commercial crew but also the Space Launch System, Orion and other elements of the Artemis program. She succeeded Doug Loverro, who resigned after less than six months amid questions about his role on the Human Landing System procurement.

“I’ve always been impressed with her ability to lead teams and her technical competence,” NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said at a briefing about Lueders’ promotion. “The whole world saw that level of skill and capability when they watched the commercial crew launch.”

Lueders is the first woman to lead NASA’s human spaceflight programs, but she said she initially overlooked that milestone. “I was more overwhelmed with the tasks in front of me,” she said shortly after taking the job. But she thought more about it after getting congratulatory notes from many women. “It helped me realize what the power of me being first means to them. They’re able to see themselves in me, and I’m very honored by that.”

– back to top –

Large Company of the Year – NORTHROP GRUMMAN

Mergers of large companies often promise synergies that fail to be realized. So there was certainly skepticism about Northrop Grumman’s acquisition of Orbital ATK, a $9.2 billion deal that closed in 2018. However, it’s now clear that Orbital ATK’s capabilities, from rocket motors to satellites, have bolstered Northrop’s space business.

A prime example: Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD). The massive Pentagon program to replace the nation’s strategic nuclear missiles was supposed to be a two-horse race between Northrop Grumman and Boeing. But by mid-2019, Northrop had the field to itself thanks in large part to its acquisition of Orbital ATK, the nation’s leading supplier of solid rocket motors.

Boeing dropped out of the competition in July 2019, saying it couldn’t credibly compete against Northrop’s price advantage as the newly dominant player in solid rocket motors.

Northrop’s decision to expand its space portfolio and add rocket propulsion to the mix by buying Orbital ATK more than paid for itself this September when the U.S. Air Force awarded the company $13.3 billion to develop a new ICBM. Follow-on contracts could fetch tens of billions more over several decades.

Orbital ATK also gave Northrop a foothold in satellite servicing, commercial satcom and human spaceflight. The company has become the first commercial provider of in-space satellite servicing with the Mission Extension Vehicle. In February, the MEV-1 made a first-of-its-kind docking with Intelsat IS-901, taking over stationkeeping for the aging satellite. A second vehicle, MEV-2, launched in August and will dock with the Intelsat IS-10-02 satellite in early 2021.

Northrop also fared well booking orders for new satellites. In this year’s C-band bonanza, it won four orders — more than any contender besides Maxar.

In human spaceflight, Northrop has found new applications for the Cygnus cargo tug originally developed by Orbital ATK for space station resupply missions. The HALO module it is developing for NASA’s lunar Gateway draws upon Cygnus heritage, as does the transfer module it is developing as a member of Blue Origin’s human lunar lander team.

Not every new endeavor has been successful. Before it was merged into Northrop Grumman, Orbital ATK had started developing a heavy-lift rocket dubbed OmegA to compete for Pentagon launches. While Northrop won nearly $800 million in 2018 to work on OmegA, the company pulled the plug on the project after the Air Force decided in August to stick with United Launch Alliance and SpaceX as its two main launch providers.

Even without OmegA, Northrop has a piece of the military launch market — as operator of the Minotaur rocket and as the supplier of strap-on boosters for ULA’s Vulcan Centaur. On the civil space side, it will produce heavy-lift boosters for NASA’s Space Launch System.

Northrop’s legacy space business, meanwhile, worked through the pandemic to keep the $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope on track for a 2021 launch — albeit one that has slipped from March to October.

On the military side, Northrop has a share of the Pentagon’s latest procurement of early warning satellites, a market that has been dominated by Lockheed Martin. Northrop is currently building two of the five Next-Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared satellites the Space Force plans to start launching in 2025.

Given the success of the GBSD competition, ongoing NASA programs and new commercial space capabilities, Northrop’s purchase of Orbital ATK is looking like a bargain.

– back to top –

Small Company of the Year – ICEYE

Like most companies, Iceye had to rewrite its playbook for 2020. Still, the Finnish radar satellite operator managed to raise $87 million, roll out new products and expand its global footprint.

Iceye spun off from Aalto University in 2014 when founders Rafal Modrzewski and Pekka Laurila began working with ExxonMobil to test whether aerial imagery from their small synthetic aperture radar could discriminate among different types of ice in the Arctic. When that test was successful, the startup began raising money for a more audacious goal: mounting the synthetic aperture radar on a microsatellite.

At the time, only large corporations and government agencies built and operated radar satellites capable of gathering imagery around the clock and through clouds. Conventional wisdom suggested a satellite weighing less than 100 kilograms couldn’t provide enough power or house a large enough antenna.

After a painstaking four-year effort, Iceye proved naysayers wrong with Iceye-X1 launched in early 2018. Iceye launched four more satellites in 2018 and 2019, while establishing subsidiaries around the world.

The company’s general engineering and management offices are in Helsinki. Operations, customer service and FPGA programming personnel work in Warsaw. Iceye Information Systems UK Ltd. has sales offices in Guildford and Harwell. In 2020, Iceye established a U.S. office and began scouting locations for a U.S. manufacturing site.

In the midst of a pandemic that delayed launches and complicated the task of manufacturing satellites, Iceye’s most impressive 2020 achievement was closing an $87 million Series C investment round, bringing the firm’s funding total to $152 million.

With money in the bank, Iceye’s leaders can now focus on their ultimate goal: expanding the constellation to offer multiple daily images of specific targets.

When 2020 began, Iceye planned to double the size of its constellation of three 100-kilogram satellites. The pandemic has made that difficult but Iceye managed to launch two satellites and more launches are scheduled in early 2021.

In the meantime, Iceye continues to update its technology and unveil new products. With every new satellite, Iceye builds on the heritage and lessons learned from its predecessors.

Iceye also keeps expanding its product line. In 2020, Iceye unveiled a product to help customers identify ships at sea that turned off transponders, a video-like product that shows multiple images of a single location captured in a single satellite pass, imagery with a resolution of 25 centimeters acquired from a single satellite staring at a location for 10 seconds and an interferometric capability.

In 2020, Iceye also joined the International Charter: Space and Major Disasters, which provides satellite data to communities responding to natural or human-made disasters. And Iceye began distributing data to principal investigators through the European Space Agency’s Earthnet Third Party Missions.

– back to top –

Large Company Leader of the Year – TORY BRUNO

When Tory Bruno took the reins of United Launch Alliance in 2014, the Boeing-Lockheed Martin joint venture faced threats on several fronts that put the launch provider’s future existence in doubt.

SpaceX was challenging its near-monopoly in the national security launch market, the U.S. Air Force and Congress were up in arms over high launch prices, and deteriorating U.S.-Russian relations meant ULA needed to figure out an alternative to relying on Russian RD-180 engines to launch some of the nation’s most sensitive satellites.

Bruno responded to these headwinds with Vulcan, a heavy-lift rocket powered by a made-in-America engine competitively sourced from another billionaire-backed rival, Blue Origin.

In addition to taking on the enormous technical risks of building a new rocket, Bruno had to convince ULA’s corporate parents the investment would keep it in an increasingly competitive game.

He made the case that ULA could replace its workhorse Atlas 5 and the less-used Delta 4 Heavy with a single rocket, reducing overhead costs and making Vulcan a viable contender. Vulcan would have to compete on reliability — ULA’s key selling point, with more than 140 consecutive successful launches under its belt — and find a way to hold its own on price against famously low-cost SpaceX and its increasingly reusable Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets.

Bruno pitched Vulcan as tailor-made for national security missions but still suitable for commercial markets. In 2019, Vulcan secured two commercial customers: Astrobotic’s robotic lunar lander slated to go to the moon in 2021, and Sierra Nevada’s Dream Chaser uncrewed spaceplane, scheduled to make the first of two ULA-assisted space station cargo runs in 2022.

ULA’s main goal, however, was to secure the U.S. military as Vulcan’s anchor customer. That meant making sure ULA was one of two winners of a four-way competition for a Pentagon’s launch contract that runs through 2027.

Bruno’s Vulcan bet paid off in August when the U.S. Air Force picked ULA and SpaceX as its two National Security Launch Program Phase 2 providers. ULA got the top score in the competition, edging out SpaceX to claim a 60 percent share of the up to 35 missions covered under the contract.

Reflecting on what made this win possible, Bruno said: “The most important decision was to stick to our core national security market and our mission success culture.”

To position ULA to compete for Phase 2, Bruno had to downsize the workforce, consolidate facilities and make adjustments to the supply chain. As he put it: “We had to face our new market challenges head-on and fearlessly embark into a fundamental transformation of our company.”

Vulcan program manager Mark Peller describes Bruno as a “visionary leader with a very strong technical background and a tremendous amount of operational experience.”

For Vulcan to be competitive, Peller said, ULA had to “transform the entire enterprise.” Bruno’s guidance helped the company come up with new ways of building and launching rockets and he motivated the workforce to be more agile.

ULA’s transformed enterprise will be put to the test in the years ahead. For starters, it must safely and reliably fly out its Atlas 5 and Delta 4 Heavy manifests — including Boeing’s Starliner crew demo flight, ULA’s first time launching astronauts — while getting Vulcan ready for its 2021 debut.

What’s more, Vulcan must complete two successful launches before it is certified to fly a pair of Pentagon launches in 2022, the first assigned to ULA under its NSSL Phase 2 contract.

Meeting that goal is hugely dependent on Blue Origin completing BE-4 development and delivering production versions of Vulcan’s main engine. It’s crunch time, and Bruno knows it. “We must now make good on our promises.”

– back to top –

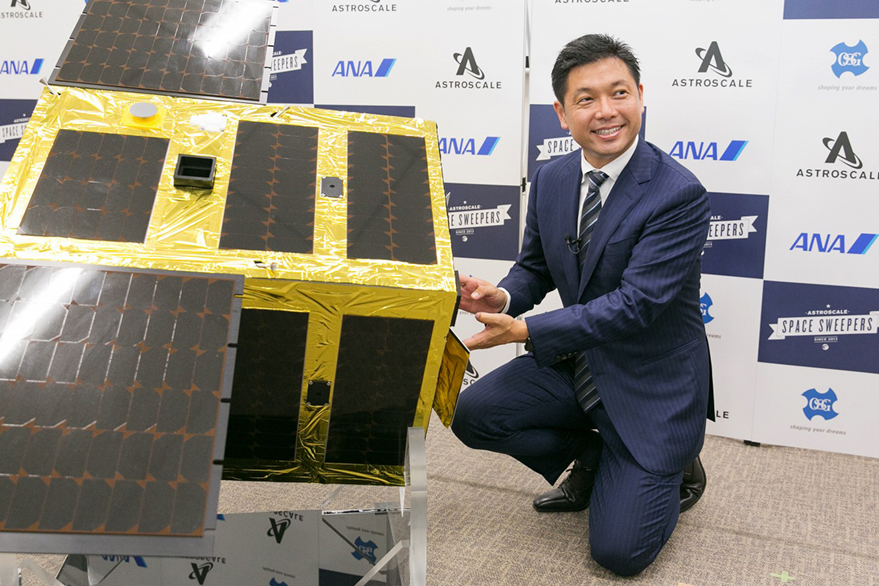

Small Company Leader of the Year – NOBU OKADA

Nobu Okada’s commitment to making space ventures safe and sustainable is heartfelt, which may explain his remarkable success in sharing his vision with employees, customers and investors.

During 2020, a year of daunting challenges for companies around the world, Astroscale, the firm Okada founded in 2013 and leads as CEO, compiled a remarkable list of accomplishments.

Astroscale closed a $51 million funding round, bringing its total investment to date to $191 million. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government awarded Astroscale a $4.5 million contract to create a road map for commercializing space debris removal services.

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency selected Astroscale to inspect a discarded Japanese rocket upper stage, a precursor to a mission to remove it from orbit. Astroscale also won the Grand Prix during the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s Netexplo Innovation Forum, a showcase for digital innovations that promise profound and lasting societal impacts.

Company executives attribute the string of successes to Okada’s leadership and his ability to communicate his vision for a future where companies and government agencies work together to stop creating orbital debris, remove objects that pose a threat to spacecraft and conduct activities in a manner that preserves space access for future generations.

Before Astroscale, Okada worked in Japan’s Ministry of Finance and consulting firms. He also founded two IT startups before a midcareer crisis reminded him of his childhood passion for space.

As a teenager, Okada traveled from Japan to attend space camp at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama. There, he met Japan’s first astronaut, Mamoru Mori, who handed him a note that read, “The challenge of space is waiting for you.”

When Okada founded Astroscale decades later, he identified a formidable challenge: cleaning up space debris. Not only was the technology lacking or unproven, there also were significant regulatory and political impediments to active debris removal.

Astroscale has cleared some of the impediments and is preparing to show its technological prowess with End-of-Life Services by Astroscale-demonstration (ELSA-d), the first commercial orbital debris removal mission. Through the 2021 ELSA-d mission, Astroscale plans to demonstrate core technologies necessary for space debris capture and removal.

Since Astroscale began planning the ELSA-d mission, Okada’s vision for the company has broadened to include inspecting, maintaining, upgrading and extending the life of satellites in orbit. In June, Astroscale acquired the intellectual property and hired the staff of Effective Space Solutions, a startup developing a satellite servicing vehicle.

“By 2030, I want to make on-orbit servicing routine work, a normal service in space that happens every day,” Okada said in September at the Secure World Foundation Summit for Space Sustainability. “To do that, we have only 10 years and there are many things to do.”

Fortunately, Okada is not tackling that challenge alone. Astroscale employs 154 people in five countries: Singapore, Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom and Israel.

Astroscale executives around the world also play key roles in the global conversation about debris removal and satellite servicing, led by Okada who serves as vice president of the International Astronautical Federation and co-chair of the World Economic Forum Global Future Council on Space.

– back to top –

Startup of the Year – YORK SPACE SYSTEMS

When the Pentagon’s Space Development Agency selected two companies to produce satellites to communicate with one another and relay data to military forces on the ground, at sea and in the air, one of the winners was Lockheed Martin, a government contractor with decades of spaceflight experience. The other company chosen to manufacture satellites for Transport Layer Tranche 0 was York Space Systems, a startup founded in 2015.

Alumni from NASA, the Defense Department, Lockheed Martin, Orbital ATK and Ball Aerospace established York Space Systems to slash the cost of satellites and increase their reliability through mass manufacturing. Rather than designing satellites to meet each customer’s unique requirements, York Space Systems seeks to replicate Ford Motor Co.’s successful Model-T program by continually producing S-Class, a reliable three-axis-stabilized satellite for payloads of 85 kilograms.

Maintaining a satellite production line also helps speed up delivery. In May, York Space Systems moved into a Denver facility three times the size of its previous plant. The new facility is large enough for employees to manufacture and test 20 to 25 spacecraft per year. By the end of 2021, York plans to produce 50 satellites per year and have the ability to deliver satellites to customers within months of contract signing.

The first York Space Systems satellite to reach orbit was the U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command’s Harbinger mission. The 150-kilogram satellite with a synthetic aperture radar and high-bandwidth downlink launched in 2019 on a Rocket Lab Electron rocket.

Since that launch, York has received dozens of government and commercial satellite orders, and expanded its product line to offer turnkey services. Customers can hire York for payload integration, testing, launch services and mission operations.

Early this year, York also announced plans for the Hydra Mission Series to help customers rapidly gain flight heritage by launching payloads, subsystems and components in S-Class satellites.

York does not announce contract awards, preferring to let customers decide what information to disclose publicly. As a result, we don’t know the names of many of York’s government and commercial customers.

We do know, however, that the Space Development Agency awarded York a $94 million contract in August for 10 Transport Layer Tranche 0 satellites to launch in 2022. Lockheed Martin is manufacturing another 10 Transport Layer Tranche 0 satellites for $187.5 million.

Lockheed Martin and York offered “just an outstanding technical solution, with a good focus on schedule because they know that’s important,” SDA Director Derek Tournear told reporters in an August video conference. “We awarded them based completely on the technical merit and what we thought was their ability to be able to make schedule and provide a solution.”

– back to top –

Space Stewardship Award – SECURE WORLD FOUNDATION

With a staff of 12 people, the Secure World Foundation plays an outsized role in the global dialogue on space stewardship, offering information and insight on sustainability, law, policy and security.

In 2020 alone, SWF hosted 41 events including its flagship Summit for Space Sustainability, a three-day virtual event that attracted several hundred participants from dozens of countries as well as notable speakers from international government agencies, industry and academia.

When SWF was established in 2002 by Marcel Arsenaul and Cynda Collins Arsenault, it promoted the concept of space sustainability primarily in the United States. However, the organization quickly gained a reputation for providing information and insight to public and private organizations around the world.

For years, SWF has worked extensively with the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) and the First Committee, which focuses on issues related to international security and disarmament. Before becoming SWF executive director in 2018, Peter Martinez chaired the COPUOS Working Group on the Long-Term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities.

Increasingly, SWF shines a light on military space activities. Brian Weeden, Secure World Foundation program planning director, and Victoria Samson, SWF Washington office director, assess publicly available information on direct-ascent, co-orbital, electronic warfare, directed energy and cyber weapons in their annual report Global Counterspace Capabilities: An Open Source Assessment.

SWF also plays key roles in organizations created in recent years to establish guidelines and standards for space operations. SWF was a founding member of the Space Safety Coalition, a group of international satellite operators and organizations that formed in 2019 to endorse a set of best practices to minimize the risk of in-orbit collisions and to encourage satellite operators to deorbit spacecraft within 25 years. In addition, SWF worked with DARPA, Advanced Technology International, the University of Southern California’s Space Engineering Research Center and the Space Infrastructure Foundation to establish in 2018 the Consortium for Execution of Rendezvous and Servicing Operations, an industry-led group that develop consensus technical and safety standards for in-orbit servicing.

Organizations new to the space sector often turn to SWF for guidance. Since 2017, SWF has published the Handbook for New Actors in Space, an overview of space-related principles, laws, norms of behavior, standards and best practices. The handbook has proved to be so popular that SWF published a Spanish edition in 2019 and SWF is working on French and Chinese editions.

All the data for 2020 has not yet been compiled, but SWF’s 2019 accomplishments offer a snapshot of this industrious organization. In 2019, SWF employees created 124 reports, presentations and other resources. SWF also hosted or participated in 102 conferences, meetings and other events in the United States and Canada, Europe, the Asia-Pacific region, Africa, the Middle East and Oceania as well as virtual events.

SWF is based in Broomfield, Colorado, and has an office in Washington.

– back to top –