SpaceNews established these awards to honor the well-known champions and the unsung heroes shaping the global space industry. We endeavored to celebrate headline-grabbing breakthroughs as well as outside-the-limelight innovations.

The winners recognized in the pages ahead were chosen by the SpaceNews editorial team after an open nomination process that concluded with a reader poll.

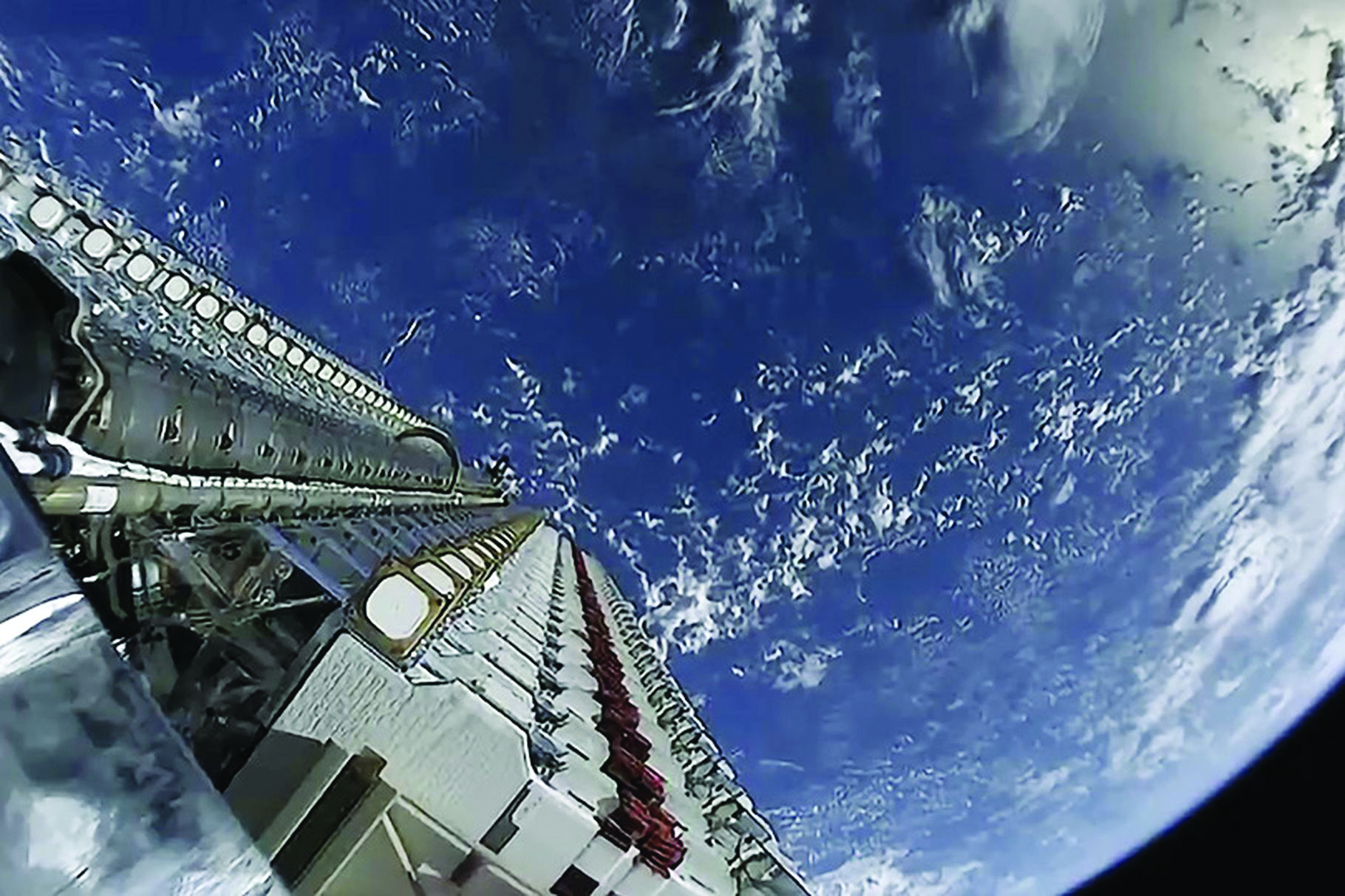

STARLINK

Readers’ Choice

- SpaceX’s Starhopper

Anyway you slice it, the world’s leading launch provider can now claim the world’s largest satellite telecom constellation. SpaceX, which conducted a record 21 launches in 2018, took just two launches to deploy 120 of its Starlink broadband satellites into low Earth orbit this year.

Although SpaceX aims to deploy at least 12,000 Starlink satellites by the mid-2020s in a bid to blanket the globe with abundant, low-latency satellite broadband, SpaceX founder Elon Musk says the first 120 satellites alone can deliver a combined 2,000 gigabits per second of useful network capacity. That makes SpaceX’s fledgling Starlink constellation nearly eight times more powerful than ViaSat-2, the highest capacity satellite broadband system currently in service.

And while traditional operators have next-generation geostationary satellites in development for 2021 promising 1,000 Gbps of throughput, SpaceX stands to add an equivalent amount of useful capacity to its Starlink constellation each time a Falcon 9 launches another 60-satellite batch into low Earth orbit. With two dozen such launches on the books for 2020, SpaceX is poised to rapidly expand Starlink’s lead in on-orbit capacity and download speeds.

Starlink satellites have already shown they can deliver 610 megabits per second of secure connectivity to U.S. military aircraft, making Starlink’s demonstrated in-flight downloads six times faster than the average U.S. internet connection and 25 times faster than the FCC’s 25 Mbps threshold for services advertised as broadband.

Starlink is just several launches away from achieving sufficient coverage to roll out regional service. However, SpaceX has yet to announce customers or unveil affordable user terminals. Although LEO megaconstellations like Starlink won’t suffer the same signal lag and slower speeds that tend to make GEO broadband a last-resort solution, they need a lot more satellites to provide continuous service over comparable coverage areas. That, in turn, creates a bevy of problems, including the need for more sophisticated user terminals than the relatively cheap set-and-forget dishes that work with geostationary satellites.

Like all breakthroughs, Starlink comes with its share of challenges. In September, the European Space Agency was given a scare when a deliberately deorbiting Starlink with its collision avoidance system turned off was due to pass uncomfortably close to ESA’s Aeolus satellite. Unable to reach SpaceX, ESA decided to maneuver Aeolus and then tweeted its dismay. SpaceX has said it will tighten protocols for coordination with other operators.

SpaceX has also vowed to make Starlink less reflective, a pledge meant to address astronomers’ concerns that telescope observations could be disrupted by the unprecedented number of satellites soon to be transiting the night sky.

It remains to be seen whether Starlink can achieve commercial success without proving a nuisance. But with just a tiny fraction of its constellation on orbit, SpaceX has again shown its knack for disrupting markets and putting the competition on notice.

FIREFLY AEROSPACE

Readers’ Choice

- Maxar Technologies

Three years ago, things were looking dire for Firefly Space Systems. After an unnamed investor backed out of a new funding round, the company furloughed nearly its entire staff of 150 people, halting developing of its Alpha small launch vehicle. The company was on a path to bankruptcy and liquidation.

But in business, there can be life after death. One of Firefly’s creditors, Noosphere Ventures, acquired the company’s assets in an auction in 2017. Noosphere reconstituted the company, bringing back many of the original employees, including chief executive Thomas Markusic, under the name Firefly Aerospace.

Today, Firefly is closer than ever to realizing its original vision of a low-cost small launcher. At a site outside of Austin, Texas, the company is performing static-fire tests of the two stages of the Alpha launch vehicle, capable of placing up to a ton of payload into low Earth orbit for $15 million. Firefly is modifying a launch pad at Vandenberg Air Force Base formerly used by the venerable Delta 2 for Alpha, with a first launch now expected in the first quarter of 2020.

The company’s projects, though, don’t stop with Alpha. On the drawing board is Beta, a medium-class launch vehicle with a payload capacity of eight tons to LEO. In October, Firefly announced a partnership with Aerojet Rocketdyne that includes studying the use of Aerojet’s AR1 engine to power the first stage of Beta. That agreement covers the use of other Aerojet technologies, such as in-space propulsion systems for an orbital transfer vehicle Firefly is also proposing to develop.

The company’s ambitions extend to the moon. Firefly was one of nine companies that won a Commercial Lunar Payload Services contract from NASA last year, allowing it to compete to deliver NASA payloads to the lunar surface. In July, Firefly said it was partnering with Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) to develop a lander, called Genesis. It will be based on the Beresheet lander IAI built for SpaceIL that attempted a landing in April.

Firefly is on a secure financial footing, as Max Polyakov, the founder of Noosphere Ventures, has committed to funding the company through the first Alpha launch, an amount neither he nor the company has disclosed. That doesn’t guarantee success, particularly in the crowded small launch vehicle market, but does give Firefly a fighting chance — or, in this case, a second chance.

ROCKET LAB

Readers’ Choice

- ROCKET LAB

One of the more remarkable stories in the space industry in recent years is the wave of companies working on small launch vehicles. By some estimates, more than 100 such vehicles are in development, ranging from those actively being built and tested to ones that have yet to move beyond PowerPoint presentations. Either way, it’s far more than even the most optimistic estimates of demand for launching small satellites.

One company, though, has emerged as the clear leader in the market. Rocket Lab moved into regular operations of its Electron rocket in 2019, performing six launches, all successful. While other companies continued to work on their small launchers, or suffered technical or financial setbacks, Rocket Lab launched small satellites for customers ranging from Earth-imaging company BlackSky to DARPA and the U.S. Air Force.

The year also signaled growing ambitions for Rocket Lab. It announced plans in April to develop a satellite bus called Photon, based on the Electron’s kick stage, for missions in Earth orbit or all the way to the moon. Rocket Lab also announced a partnership with KSAT to give its customers access to that company’s network of ground stations. Combined, it’s intended to provide one-stop shopping for customers planning space systems, and sets the company apart from competitors that focus only on launch services.

Rocket Lab is also investing in reusability. In its latest launch Dec. 6, Rocket Lab tested upgrades to the Electron’s first stage to control the stage through re-entry, a key step toward ultimately recovering and reusing the stage. That effort is driven by a desire to sharply increase its launch rate in the future without having to scale up its manufacturing capability by the same amount.

While it may be some time before the company reaches its goal of one launch a week enabled by reusability and other manufacturing innovations, the company expects to launch more frequently in 2020. It will also start operations from a second launch site, at Wallops Island, Virginia, early in the year, and begin flying Photon satellites. The company expects to hire more than 100 people over the next year at its facilities in the United States and New Zealand.

Rocket Lab likely will see more competition in the next year as other small launch vehicle companies enter service. The company, though, has established that there is demand for dedicated small launch services and put itself in a position to lead, and even dominate, the market for years to come.

HAWKEYE 360

Readers’ Choice

- Relativity Space

When HawkEye 360 was founded in 2015, it wasn’t clear whether a cluster of microsatellites could detect radio-frequency signals emanating from ships and planes to pinpoint their precise locations. But Chris DeMay was optimistic.

After 14 years working in U.S. defense and intelligence agencies, DeMay saw startups capturing optical imagery with small satellites and thought miniature spacecraft could employ similar technology to home in on RF signals. To find out, DeMay teamed up with software, signal processing and analytics experts, and John Serafini, a technology investor and startup leader who became HawkEye 360’s CEO.

Earlier this year, the Herndon, Virginia, startup announced the results on Twitter. HawkEye 360’s three Pathfinder satellites launched in December 2018 were “successfully geolocating a diverse variety of RF signals!” according to the Feb. 26 tweet. The Pathfinder satellites, built by the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies (UTIAS) Space Flight Laboratory and equipped with software-defined radios, fly in formation 100 to 200 kilometers apart. When all three satellites tune into the same signal, the firm’s algorithms identify the type of RF emitter and its location.

After announcing that its Pathfinder constellation worked as intended, HawkEye 360 began unveiling products for its intended audience: defense and intelligence agencies, maritime organizations, telecommunications providers and emergency responders. RFGeo, for example, is a product the company unveiled in April to help customers identify and geolocate maritime VHF radio channels, marine emergency distress beacons and vessel Automatic Identification System signals. In October, HawkEye 360 released an updated version of RFGeo to detect UHF band communications, including push-to-talk radios often used by cross-border smugglers and poachers in nature preserves.

In recent months, HawkEye 360 has stepped up fundraising. Its $70 million Series B round announced in August attracted venture capital firms as well as Airbus Defence and Space and ESRI, the geographic information system software giant. Raytheon Corp. led the startup’s $14.9 million Series A-3 round in 2018. Overall, HawkEye 360 has raised more than $100.

With money in the bank, HawkEye 360 is turning its attention to expanding its constellation. The startup plans to operate six clusters of three satellites each to provide frequent daily observations of RF activity. The Series B round provides the company with enough money to build and launch its next five satellite clusters, Serafini said in a recent interview. HawkEye 360 is preparing to launch its next three-satellite cluster early next year. UTIAS Space Flight Laboratory is on contract to manufacture the next 15 satellites in the HawkEye 360 constellation.

NASA

Readers’ Choice

- NASA

At the beginning of this year, NASA was moving ahead with plans to return humans to the moon by 2028 in a methodical, deliberate way. It was in discussions with international partners on providing modules for the lunar Gateway that, once complete, would serve as a base camp for those lunar landings. In early February, NASA solicited proposals for lunar lander studies. Those proposals were due to NASA March 25.

The next day, everything changed. In a speech at a National Space Council meeting in Huntsville, Alabama, Vice President Mike Pence instructed NASA to accelerate its human return to the moon, landing within the next five years. Pence cited potential competition from China as one reason for speeding up those plans, as well as “racing against our worst enemy: complacency.”

There’s certainly no complacency at NASA now. Since Pence’s speech, NASA has done a remarkable job revamping its lunar exploration plans, now known as the Artemis program, to support a 2024 landing. It accelerated work on a lunar lander while deferring much of the work on the lunar Gateway to after 2024. “At the end of the day we’re going in 2024, whatever that takes,” NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said not long after the speech.

That includes a strong reliance on commercial partnerships rather than conventional contracting. NASA plans to acquire logistics for the Gateway using the same commercial cargo model that supplies the ISS. A more ambitious step is to use such partnerships for human lunar lander development, ultimately buying landing services from companies, rather than the landers themselves.

NASA is doing all that while carrying out a full plate of other programs, like operation of the ISS, development of commercial crew, and major science missions such as the James Webb Space Telescope and Mars 2020 rover, all with their own sets of issues. Bridenstine has said on many occasions that he won’t “cannibalize” other parts of the agency to pay for Artemis.

NASA still faces technical and, perhaps more importantly, financial challenges to achieving that 2024 goal. Congress has yet to pass a 2020 spending bill, and House members in particular have been skeptical about the proposed $1.6 billion in additional funding requested to jump-start Artemis in part because the agency hasn’t yet provided an estimate of what the overall program will cost. But it’s clear that there is a new focus and urgency at NASA on returning to the moon not seen in many years.

JAN WOERNER

Readers’ Choice

- NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine

At a news conference Nov. 28 to mark the end of the European Space Agency’s ministerial meeting in Seville, Spain, Jan Woerner, director general of the agency, smiled. “You have a happy DG in front of you,” he said.

He had every reason to be happy. At the briefing, Woerner announced that ESA’s 22 member states had agreed to provide 12.45 billion euros ($13.8 billion) in funding for the next three years, just shy of the 12.5 billion euros the agency requested. Every major program that ESA proposed was funded, including some that received even more money than the agency asked for.

That two-day ministerial meeting, called Space 19+, marked the end of a two-year effort by Woerner to secure the agency’s future that started not long after the previous ministerial meeting in late 2019. “We started with a narrative, to have a clear picture of what ESA is doing,” he said in an October interview. “That was very important from my point of view.”

That narrative took the form of four “pillars” to describe all of ESA’s activities: science and exploration, applications, enabling and support, and space safety. ESA also lumped programs into three categories of rationales: competitiveness, inspiration and responsibility. For months leading up to the Space19+ meeting, Woerner took every opportunity to emphasize those pillars and those rationales as key to the agency’s, and Europe’s, future in space.

That concerted effort paid off. Member states provided funding to ensure ESA will have a role in NASA’s Artemis program beyond the Orion service module by funding initial work on two modules for the lunar Gateway and a large robotic lunar lander. Plans to cooperate with NASA on Mars sample return also won funding, as did Hera, a near Earth asteroid mission that emerged from the ashes of the Asteroid Intercept Mission, which failed to win funding at the 2016 ministerial.

The meeting wasn’t perfect — ESA’s space safety pillar got less money than requested, forcing the agency to scale back a space weather mission to an instrument development program — but Woerner played down that setback. “We intended to get more, but this is life,” he said. “It’s not a disaster, not at all.”

ESA now has to go carry out those ambitious plans, which brings with it a whole new set of challenges. Woerner, though, was able to secure the funding to make those projects possible, which is something the whole European space community can be happy about.

U.S. AIR FORCE GEN. JOHN “JAY” RAYMOND

Readers’ Choice

- U.S. AIR FORCE GEN. JOHN “JAY” RAYMOND

“This is absolutely the most exciting time to be in the national security space enterprise,” Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond is fond of saying, whether speaking to space industry CEOs, lawmakers or military troops.

Raymond, the four-star commander of U.S. Space Command and U.S. Air Force Space Command, impresses audiences with his passion and enthusiasm. It came as no surprise when President Trump in March nominated Raymond to lead U.S. SPACECOM, the newest of the Defense Department’s 11 unified commands.

For Raymond, this was a capstone achievement after 35 years serving in national security space operations at every level. By Raymond’s own account, planning for the unified command started in August 2018 when he was informed by the Pentagon that U.S. SPACECOM, which was absorbed into U.S. Strategic Command in 2002, would be reactivated. Once he got word, Raymond hunkered down with a small team to quickly formulate how U.S. SPACECOM would be organized. Raymond told a Washington audience in November that building a new command and then getting asked to lead it has been the highlight of his career.

Raymond’s imprint is evident in how U.S. SPACECOM was organized to accomplish two key missions: provide space-based capabilities to U.S. and allied commanders in the field, and ensure that those capabilities are defended against electronic or physical attacks.

One of U.S. SPACECOM’s components is a new organization that Raymond advocated for: the Joint Task Force Space Defense, which gives the U.S. military for the first time an operations-level command focused on protecting space assets. It was also at Raymond’s urging that the military and the intelligence community agreed to work more closely on space matters. Should a military conflict extend to space, the National Reconnaissance Office will take direction from the commander of U.S. SPACECOM.

The military’s space operators could not ask for a more steadfast advocate. Raymond has been a strong backer of the Trump administration’s Space Force proposal. If Congress gives the OK, a separate military service dedicated to space would absorb Air Force Space Command, freeing up Raymond to focus on his combatant commander duties.

No matter what happens next in the space reorganization, Raymond will be a leading voice on all matters related to national security space. And he will be speaking for all space operators across all branches of the military. As he put it recently: “If you’re wearing a space patch today and you’re in the United States Air Force, Army or Navy, you have an extra bounce in your step.”

DAN JABLONSKY

Readers’ Choice

- Maxar CEO Daniel Jablonsky

In his brief tenure at Maxar Technologies, Dan Jablonsky has navigated through rough water. The former naval surface warfare officer and nuclear engineer took Maxar’s helm Jan. 13, six days after the company announced the failure of its WorldView-4 Earth-imaging satellite. At the time, Maxar leaders were publicly discussing whether to sell, shutter or scale back the firm’s West Coast satellite manufacturing facility amid a global slump in geostationary spacecraft orders.

Jablonsky, who spent nearly eight years at DigitalGlobe rising to the rank of president, led a thorough evaluation of Maxar’s structure and business components. In the end, the company opted to retain the satellite manufacturing business with a smaller workforce and to turn Maxar into a single operating company except for MDA of Canada, which remains vertically integrated. Maxar also worked to expand sales to U.S. and allied government agencies and to focus its resources on WorldView Legion, the Earth imagery constellation designed to double the company’s capacity to collect satellite imagery with 30-centimeter resolution.

Maxar’s effort to attract more government work seems to be paying off. In May, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine announced Maxar would develop the Power and Propulsion Element for the space agency’s lunar Gateway under a $375 million firm fixed-price contract. Maxar’s Power and Propulsion Element, designed to provide electrical power for the Gateway and move it through cislunar space using solar electric propulsion, is based on the firm’s 1300-series flagship satellite platform.

The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) announced in June the award of a study contract of undisclosed value to Maxar as part of the intelligence agency’s effort to assess U.S. companies’ abilities to task, collect, process and deliver satellite imagery. Maxar already supplies NRO with priority access to imagery from WorldView satellites and the company’s digital archive under the $300 million a year EnhancedView Follow-On contract. Through the study contract, NRO is exploring whether U.S. defense and intelligence agencies should buy additional Maxar products and services. Maxar won another government contract in July when NASA awarded the firm $79 million to send a pollution sensor into orbit as a hosted payload on a Maxar-built commercial communications satellite.

Then in November, Maxar announced a commercial sale. An undisclosed customer ordered a geostationary communications satellite. Improved sales are helping Maxar’s financial situation. In the third quarter of 2018, the firm reported a loss of $289 million. In the third quarter of 2019, Maxar, under Jablonsky’s leadership, reined that in to a net loss of $26 million.

It’s too soon to say whether calm seas are ahead for Jablonsky. Two of Maxar’s key markets, Earth observation and satellite communications, are changing rapidly. Rather than expressing concern, Jablonsky embraces the challenge. “Ships are built to go to sea, and I’m built for an environment that is not completely safe and inside the harbor,” he said in an interview earlier this year.

VIRGIN GALACTIC IPO

Readers’ Choice

- Blue Origin’s Artemis lander “national team”

Over the last several years, billions of dollars of private investment have flowed into the space industry, from massive funding rounds by OneWeb and SpaceX to small early-stage rounds for a wide range of small launch vehicle, smallsat and other space startups. The problem is judging how lucrative those investments are: there have been few major exits, in the form of acquisitions or public offerings, that have allowed investors to get a return on their money.

That environment is what makes Virgin Galactic’s decision this year to go public so important. The suborbital spaceflight company is among the best known in the entrepreneurial space field thanks to its famous founder, Richard Branson, and its space tourism ambitions. However, development of its SpaceShipTwo vehicle had taken far longer than envisioned, and the company needed additional capital to get it into service. In July, Virgin Galactic announced it would go public, but do so in a nontraditional way.

Virgin said it would merge with Social Capital Hedosophia (SCH), a special purpose acquisition company that was already publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange. That approach, Virgin executives argued, was faster and more efficient than a traditional initial public offering (IPO) of stock. (SCH traded on the exchange under the ticker symbol IPOA, for “IPO Alternative.”) The deal raised more than $700 million for Virgin Galactic, of which about $300 million went to buy out some existing shareholders.

The rest will be used to fund operations of Virgin Galactic, which the company says will be enough to move into operations by the middle of next year, after completing a final series of tests of SpaceShipTwo. If all goes as planned, the company will be profitable as soon as 2021.

The merger closed in October, and Virgin Galactic started trading Oct. 28 under the new ticker symbol SPCE. It’s been a rough start: the company lost about a third of its value in its first month, but has more recently stabilized. Virgin executives, though, say they’re focused not on the short-term trends in the stock’s price but rather its long-term ambitions for suborbital space tourism and, eventually, point-to-point travel.

If Virgin Galactic successfully transitions into a profitable company, it may encourage other space startups to pursue IPOs of their own, traditional or otherwise, in the near future. The investors that are putting billions into those companies will want to eventually get their money back, and then some.

BROOKE OWENS FELLOWSHIP

Readers’ Choice

- Brooke Owens Fellowship

Cassie Lee, Lori Garver and Will Pomerantz were heartbroken when their 35-year-old friend Dawn Brooke Owens died of cancer in June 2016. Looking for a way to honor Owens, Lee, who led space programs at Vulcan, Garver, the former general manager of the Airline Pilots Association and former NASA deputy administrator, and Pomerantz, Virgin Galactic special projects vice president, established the Brooke Owens Fellowship.

To date, the Owens Fellowship has paired 114 young women with paid summer internships and year-long mentorships. Through the extensive and competitive application process, Owens Fellowship leaders identify undergraduate women and gender minorities passionate about aviation and space exploration.

Rather than simply focusing on grades and test scores, they look for women with wide-ranging talents like Owens, a certified pilot who attended Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and the International Space University, and worked at NASA, the White House, the FAA and the nonprofit X Prize Foundation. Outside of work, Owens performed slam poetry, raced triathlons and volunteered in Africa with children whose parents died of HIV/AIDS. In addition to submitting an essay highlighting their professional interests, Owens Fellowship applicants share a poem, song, dance or other creative composition about their character and personal interests.

Once selected, Owens Fellows, known as Brookies, are matched with internships at organizations like Ball Aerospace, Blue Origin, Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Scaled Composites, SpaceX and ULA. They also are paired with mentors who offer advice on their internships and aerospace careers. Every July, the current Owens Fellowship class travels to Washington to meet one another, work together to solve a grand challenge and speak with congresswomen, astronauts, CEOS and entrepreneurs. In the three years since Lee, Garver and Pomerantz created the Owens Fellowship, its reputation has grown dramatically. In 2019, 566 women from 15 countries applied.

“By the numbers, it will be harder to get into the Owens Fellowship class of 2020 than it was to get into, say, Caltech, MIT, or Naval Academy 2020,” Pomerantz Tweeted Nov. 24. “Our number of applications significantly more than doubled our previous high.”

It will take years to gauge the Owens Fellowship’s impact on the demographics of the male-dominated aerospace industry. For individual Brookies, though, the benefits are enormous. In a single year, they gain invaluable experience and connections. Judging by the waiting list of more than 40 companies and nonprofits eager to hire Owens Fellows, aerospace leaders see the attraction too.

LEOLABS

Readers’ Choice

- Iridium deorbits first-generation constellation

Dozens of startups are sending small satellites into low Earth orbit. One is revealing the increased congestion there. When LeoLabs spun out of the nonprofit SRI International in 2016, the Silicon Valley startup already knew it could spot debris in low Earth orbit. SRI was operating a UHF radar near Fairbanks, Alaska, for ionospheric research but its observations were hampered by noise caused by all the debris in low Earth orbit.

Mike Nicolls, SRI principal investigator for the ionosphere research, became adept at culling noise from his ionospheric data. So good, in fact, that he joined Dan Ceperley, who ran SRI’s space debris tracking program, and John Buonocore, former SRI principal research engineer and radar designer, to form a company to share the data.

LeoLab has raised about $17 million in two funding rounds. With that money, the company built a second UHF radar in Texas in 2017 and completed construction earlier this year of an

S-band radar on New Zealand’s South Island.Perhaps more importantly as the megaconstellations begin to take shape, LeoLabs is creating tools to help companies and government agencies make sense of increased activity in low Earth orbit and pull space tracking data into their operations.

Rather than defining itself as a radar operator, LeoLabs sees itself as the Google Maps of low Earth orbit. Like Google Maps, the startup created a cloud-based platform and API that allows customers like Internet-of-Things startup Swarm and the New Zealand Space Agency to monitor spacecraft, rockets and debris.

With its two UHF radars, LeoLabs tracks anything softball-size or larger, about 13,000 objects in all. The Kiwi Space Radar can see anything bigger than two centimeters, another 250,000 objects orbiting from 160 to 2,000 kilometers.

“We founded the company on the promise that we would deliver this technology,” LeoLabs CEO Ceperley told SpaceNews in October. “We’re extremely excited to show the technology that we’re going to take around the world.” With three radars online, LeoLabs pinpoints the location of objects to within 100 meters, determines their orbits and shares the data with satellite operators, regulators and insurance companies concerned about the risk to assets worth billions of dollars.

Space sustainability is a tall order with the thousands of satellites slated for launch in the next few years. It will take a village to keep collisions to a minimum. Alongside the astrophysicists, astrodynamicists and aerospace engineers in government agencies, universities and private companies keeping tabs on this global commons, is LeoLabs, a startup offering a new set of tools for low Earth orbit environmental monitoring.