SpaceNews established these awards to honor the well-known champions and the unsung heroes shaping the global space industry. We endeavored to celebrate headline-grabbing breakthroughs as well as outside-the-limelight innovations.

The winners recognized in the pages ahead were chosen by the SpaceNews editorial team after an open nomination process that concluded with a reader poll.

This year, we are also identifying the Readers’ Choice for each award to recognize the top vote getters in each category. More than 12,000 SpaceNews readers voted for this year’s slate of winners.

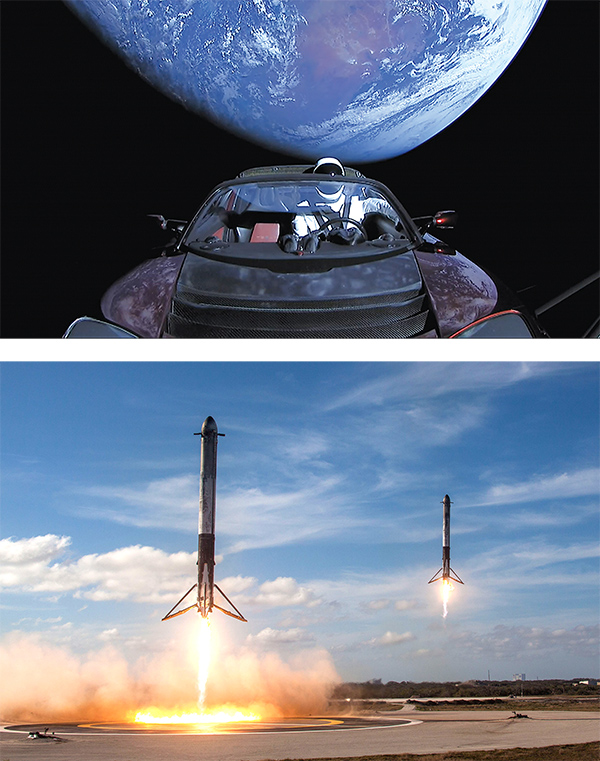

FALCON HEAVY

Readers’ Choice

- Falcon Heavy

Other Finalists

- ICEYE X-1 SAR smallsat

- NASA’s MarCO cubesats

- RemoveDebris mission

Sometimes it takes a while for a breakthrough to, well, break through. Fortunately for SpaceX and its customers, the Falcon Heavy finally delivered.

When SpaceX Chief Executive Elon Musk formally announced plans for the Falcon Heavy at an April 2011 press conference, he said the vehicle would be delivered to the company’s launch site at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California in late 2012 “with liftoff to follow soon thereafter.” Those dates, though, slipped and slipped in the following years, as the company faced development problems with the rocket and competing priorities from other programs.

At last, on Feb. 6, the Falcon Heavy took off from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39A, which previously hosted the shuttle and the Saturn 5. The rocket soared into space, and its twin side boosters made dramatic side-by-side landings back at Cape Canaveral. The rocket’s payload featured a mix of whimsy and panache characteristic of SpaceX and Musk: a Tesla Roadster electric sports car, with a spacesuit-clad mannequin at the wheel. It broadcasted live video for hours, attracting hundreds of thousands of viewers, before the upper stage boosted the car on a trajectory that took it out beyond Mars.

Musk admitted after the successful launch it almost didn’t happen. “We tried to cancel the Falcon Heavy program three times at SpaceX because it’s like, ‘Man, this is way harder than we thought,’” he said, estimating the company spent more than half a billion dollars on its development. What sort of return will SpaceX get on that investment? The market for Falcon Heavy may be limited, as upgrades to the Falcon 9 now allow it to carry payloads that previously would have required the Falcon Heavy. SpaceX also has its next-generation reusable rocket under development — formerly known as Big Falcon Rocket but recently renamed Super Heavy and Starship — with far greater performance than the Falcon Heavy.

But in the months since the Falcon Heavy made its debut, SpaceX has lined up new customers for it, attracted to a vehicle that offers to place eight metric tons into geostationary transfer orbit for just $90 million. Several commercial satellite operators have signed contracts for Falcon Heavy launches, and the U.S. Air Force certified the vehicle for national security payloads, awarding SpaceX a contract for a classified mission. For those customers, and for SpaceX, it appears that Falcon Heavy was worth the wait.

FLORIDA'S SPACE COAST

Readers’ Choice

- Florida’s Space Coast

Other Finalists

- Aerojet Rocketdyne’s AR-22

- Firefly Aerospace

- Iridium Communications

One of the clearest signs that the Space Coast region of Florida has rebounded economically from the end of the shuttle program is that there is now space commerce on Space Commerce Way.

The two-lane road had for years connected two highways just outside the gates of the Kennedy Space Center, with visions of a large business park developing there. But other than a single building, there was little activity along the road, which became primarily a shortcut by tourists going to KSC’s visitors center.

It’s a different story today. Earlier this year Blue Origin opened a 750,000-square-foot factory along Space Commerce Way that the company will use to manufacture its New Glenn rocket, which will launch starting in 2020 from Launch Complex 36 at nearby Cape Canaveral. Across the street, OneWeb Satellites, the joint venture of OneWeb and Airbus, has built a factory designed to produce the hundreds, and eventually thousands, of satellites planned for OneWeb’s broadband constellation.

Those facilities are among the biggest, but not the only, signs of a revitalization and diversification of the region’s space industry. When the shuttle program ended in 2011, bringing with it the loss of thousands of jobs, some wondered if the region would ever be able to recover. Some companies closed facilities, other businesses shut down entirely and people moved away.

One reason for the turnaround is Space Florida, the state space development agency. It offered economic incentives to attract companies like Blue Origin to the region. It’s also taking a bigger role in launch activities there, receiving an FAA spaceport license in November for the Shuttle Landing Facility runway that could host air-launch companies like Stratolaunch and Virgin Orbit.

KSC has also played a major role in the region’s turnaround. The center’s leadership has sought to turn KSC into a “multi-user spaceport” rather than serving only the needs of NASA. It worked to sign agreements to lease unneeded facilities to private companies, stimulating commercial activity while getting maintenance of them off the center’s books. Now, Boeing is building its Starliner commercial crew vehicle in a former shuttle hangar while SpaceX is launching rockets from the same pad that sent Apollo 11 to the moon.

That increase in launches by SpaceX and others has stimulated tourism in the region as well, in some cases causing traffic jams outside KSC. So, one of the projects on the drawing board is a widening of Space Commerce Way to four lanes.

IRIDIUM

Readers’ Choice

- Lockheed Martin

Other Finalists:

SpaceX

United Launch Alliance

This year, Iridium put to bed concerns about its future, working with SpaceX to launch most — and potentially all — of its second-generation satellite constellation in a span of two years. Iridium’s legacy constellation has been in space for two decades, nearly three times as long as it was designed to operate. The company’s future hinged on getting the $3 billion Iridium Next constellation in orbit and in service before the older satellites expired.

As of early December, 65 of a planned 75 Iridium Next satellites are in orbit, with the vast majority of Iridium’s telecom traffic running through the new fleet. The eighth and final batch of 10 satellites are due to launch in the coming weeks.

Iridium, meanwhile, is deorbiting legacy satellites as they are taken out of service, setting a good example of responsible orbital stewardship for the many new companies proposing large constellations of their own.

And as Iridium Next takes off, so is Iridium’s revenue. The company reported $135 million in revenue for the three months ending in June, setting a personal record it beat by $2 million during the following three months. Whereas doubts about Iridium’s business model plagued the company around the launch of its first-generation system in the late 1990s, the atmosphere around Iridium today is one of technical and financial optimism. Iridium’s stock, worth $11.60 at the beginning of 2018, has nearly doubled in value as investors shed fears about constellation deployment and look toward a future where Iridium’s expertise in machine-to-machine satellite communications evolves to serve a growing Internet of Things market.

This was also a major year for Iridium in maritime, where a five-year effort paid off with the company finally achieving a key safety certification from the United Nations. The certification means Iridium is the only company besides rival Inmarsat that can provide Global Maritime Distress Safety System services that are required for most ocean-going vessels on international trips.

In aviation, Aireon — the flight-tracking startup Iridium founded to help finance its constellation — raised $69 million this spring and began paying Iridium for hosting its sensor network onboard its satellites.

Once Iridium’s final batch of Iridium Next satellites is in orbit, Iridium will shift focus to its next big challenge: deleveraging. Iridium is poised to enjoy a capital expenditure holiday lasting at least a decade as it pays down the $2.1 billion debt it incurred deploying the second-generation constellation it’s now just one launch away from completing.

ROCKET LAB

Readers’ Choice

- Rocket Lab

Other Finalists

- Blue Canyon

- Capella Space

- Kepler Communications

- Relativity Space

It remains to be seen whether there’s a lot of money to be made in the emerging small launch vehicle market. One company, though, has demonstrated that it’s possible to raise a lot of money for small launch vehicles.

Rocket Lab announced Nov. 15 that it has raised $140 million in its latest funding round, from investors as diverse as venture capital firm Bessemer Venture Partners and the Accident Compensation Corporation of New Zealand, the country’s leading insurer. The company has now raised $288 million, valuing the company at more than $1 billion — a unicorn in the lingo of Silicon Valley.

That new funding round came less than a week after Rocket Lab performed the first commercial launch of its Electron rocket, placing into orbit several small satellites for customers like Fleet, GeoOptics and Spire. More customers are waiting in the wings, including NASA, who has a contract for a launch of a collection of smallsats as soon as December.

With the Electron having demonstrated its capabilities, and with the new funding in hand, Rocket Lab is ready to pick up the pace of operations. In October the company opened a new 80,000-square-foot factory in Auckland, New Zealand, that will be used to assemble the Electron, with the ability to produce one Electron a week. Days later, the company announced it will build a second launch site at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport on Wallops Island, Virginia, that will be ready to host launches in the third quarter of 2019. The company said its new funding round will allow it to build additional launch pads at its existing New Zealand launch site as well, while also supporting unspecified research and development projects.

Rocket Lab is hardly alone in the small launch vehicle field: dozens of other vehicles are in development around the world, including some soon to begin flights. Virgin Orbit is planning a first launch of its LauncherOne vehicle in early 2019 while Vector, which raised $70 million in October, is planning its first Vector-R launch in the coming months.

With all those vehicles in development, but uncertain demand from smallsat companies, some in the industry predict there will be a shakeout in the coming years. If so, Rocket Lab, with an operational launch vehicle and a war chest of funding, is well positioned to be one of the companies that survives that shakeout. Its investors certainly believe so.

EUROPEAN SPACE AGENCY

Readers’ Choice

- NASA

Other Finalists

- Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency

- U.K. Space Agency

- UAE Space Agency

The European Space Agency overcame enormous technological challenges to launch two ambitious missions in 2018: BepiColombo’s voyage to Mercury and the Aeolus wind-sensing satellite.

BepiColombo began its seven-year journey in October with its European and Japanese orbiters mounted on an ESA transporter. The launch was the culmination of nearly two decades of work on a $2 billion program that was nearly derailed by the complexity of its ion-electric propulsion system and the challenge of finding materials durable enough to withstand lengthy exposure to temperatures as high as 450 degrees Celsius. ESA persevered with help from more than 30 companies in 12 of its member states. In many cases, the firms had to invent technology for the mission that project manager Ulrich Reininghaus compared to flying into a pizza oven.

If by comparison Aeolus seems almost easy, it wasn’t. Program managers struggled for more than a decade with the satellite’s Atmospheric Laser Doppler Instrument (Aladin), the first space-based instrument capable of measuring wind in cloud-free atmosphere. Aladin combines an ultraviolet laser and large telescope with an extremely sensitive receiver to provide the first global vertical wind profiles. Prior to Aeolus, wind in cloud-free atmosphere was “the largest data gap in meteorology,” said Josef Aschbacher, ESA’s director of Earth observation programs.

Also in 2018, ESA continued to produce state-of-the-art Earth observation and navigation satellites. In April, Eumetsat and the European Union launched Sentinel-3B, a sophisticated ocean-monitoring satellite for the Copernicus constellation. ESA and the European Union sent four Galileo global navigation satellites into orbit in July. Then, Eumetsat completed its ESA-built constellation of MetOp polar-orbiting weather satellites in November. On the launch front, it was a rough start. In January, the ESA-backed ArianeGroup’s Ariane 5 rocket sent SES-14 and Al Yah-3 short of their intended orbits. With subsequent Ariane 5 and Vega launches, though, the ArianeGroup and Avio vehicles proved dependable. ESA, ArianeGroup and Avio also made steady progress on their next-generation rockets: Ariane 6, a rocket slated to fly for the first time in 2020, and Vega C, the light-lift launch vehicle scheduled for initial takeoff in 2019.

WILLIAM GERSTENMAIER

Readers’ Choice

- Jim Bridenstine, NASA

Other Finalists

- Mohammed Al Ahbabi, UAE Space Agency

- Jan Woerner, ESA

NASA’s human spaceflight programs have experienced enough changes over the last decade to give someone whiplash, from the Vision for Space Exploration’s return to the moon to an emphasis on Mars and, now, back to the moon again. Those efforts have had one constant, though: the person in charge.

William Gerstenmaier — known universally within and outside NASA simply as “Gerst” — became associate administrator for space operations at the agency in 2005, and took on his current role as head of NASA’s human exploration and operations mission directorate in 2011 when NASA merged space operations with exploration. It’s the culmination of a NASA career that started as an engineer at the Lewis (now Glenn) Research Center in 1977 and included leadership positions on the shuttle and International Space Station programs.

In his position, he has oversight of all of NASA’s human spaceflight activities: the ISS, the Space Launch System and Orion, commercial crew and planning for human missions beyond Earth orbit, each with its set of technical and programmatic challenges. Moreover, during his tenure NASA’s overarching plans for human spaceflight have undergone changes, from the Obama administration’s “Journey to Mars” to the Trump administration’s renewed focus on the moon. The Asteroid Redirect Mission has come and gone, but the lunar Gateway is now taking shape. Even a long-running program like the ISS has seen its share of issues, like the October Soyuz launch abort and ongoing debate about ending federal funding of the station in the mid-2020s.

Through all these challenges, large and small, Gerstenmaier has provided stability and continuity, giving confidence to the agency’s workforce and reassurances to industry and Congress. He’s embraced changes, though, such as the greater use of partnerships with the private sector. He’s backed plans to take a more commercial approach to the Gateway’s first module, the Power and Propulsion Element, which will be based on a commercial satellite bus. “We don’t need a unique spacecraft design. We don’t need a unique bus,” he said at an advisory group meeting this summer, countering the agency’s tendencies to develop unique vehicles.

His endorsement of those Gateway plans at that meeting quieted skepticism from some committee members: when Gerst speaks, people listen. That leadership has been, and will continue to be, essential as the future of NASA’s human spaceflight program takes flight in the next few years with the first SLS/Orion and commercial crew missions.

U.S. AIR FORCE SECRETARY HEATHER WILSON

Readers’ Choice

- Heather Wilson

Other Finalists

- Mike Griffin, OSD

- Betty Sapp, NRO

U.S. Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson would be one of the first to admit that no one really knows whether President Trump’s call for a Space Force will result in a full-fledged sixth branch of the U.S. military or something more like a Space Corps that would be part of the Department of the Air Force the way the Marine Corps is part of the Navy.

“We support the president’s proposal,” Wilson said in September. “But none of this can happen without Congress’ involvement, obviously.” As a former member of the House Armed Services Committee, she understands that only Congress has the authority to establish a new military service to stand alongside the Army, Air Force, Navy, Marines and Coast Guard. As an Air Force Academy graduate and doctor of international relations who served at the White House National Security Council during the collapse of the Soviet Union, she knows as well as anyone in Washington what’s at stake for the United States and its allies in the unfolding ‘great power competition’ with its geopolitical rivals.

Wilson possesses a sophisticated understanding of both the technical and political challenges involved in defending against counterspace threats posed by China, Russia and other potential adversaries.

Well before the president’s Space Force fixation threw the Pentagon for a loop, Wilson had already made it her mission to transform the way the Air Force organizes and equips its air, space and cyber forces to prevail in the 21st century’s inevitably multi-domain conflicts. Specific to space, Wilson championed SMC 2.0, a long-overdue reorganization of the Space and Missile Systems Center to empower smarter and faster delivery of vital capabilities such as a new generation of missile-warning satellites.

Air Force space modernization efforts are well funded heading into 2019, thanks to Wilson getting the White House to request a 20 percent spending increase Congress largely honored this fall. Next year’s budget battle promises to be much tougher as the Pentagon strives to balance the president’s demand to stand up a Space Force with his call for five percent across-the-board cuts.

Regardless of how the Space Force debate unfolds in the months ahead, the Air Force is fortunate to have a leader as savvy, steady and well-respected as Heather Wilson at the helm.

As one SpaceNews reader put it: “Wilson understands the loudest person in the room does not always bring forth the best ideas but instead leverages critical thinking skills of a team to build the most productive answers to our nation’s hardest challenges.”

STEPHEN SPENGLER

Readers’ Choice

- Tory Bruno, United Launch Alliance

Other Finalists

- Bob Smith, Blue Origin

- Matt Desch, Iridium Communications

The only thing more shocking than Intelsat’s pitch to let cellular networks use the satellite industry’s prized C-band spectrum for 5G was that Intelsat also got three of the world’s largest satellite operators to join it.

C-band spectrum is globally employed for satellite television broadcasts and other telecom services, being favored in particular for its signal strength during rainstorms. Cellular companies have for over a decade sought to wrest those frequencies away from satellite operators to use in their own networks.

Satellite operators have stood their ground against this front in the past, so Intelsat’s proactive move, with chipmaker Intel, to relinquish some C-band spectrum was unprecedented. Instead of preparing for regulatory fisticuffs as per norm, Intelsat under the leadership of CEO Stephen Spengler offered an olive branch, and one that could draw in billions of dollars to boot.

Initial industry reactions varied from circumspect to severe. Eutelsat CEO Rodolphe Belmer first described Intelsat’s move as one that had “taken everyone by surprise.” One regional operator called it a “disaster for the whole industry.” Telesat this spring was poised to “oppose it vigorously.”

Since then SES, Eutelsat and Telesat, the three operators besides Intelsat with the most at stake in the U.S. where Intelsat’s plan is focused, have all backed that plan through a group they formed called the C-Band Alliance.

It remains too early to tell how effective the C-Band Alliance will be in persuading the U.S. Federal Communications Commission to accept their plan, which involves allowing mobile networks to use 180 megahertz (36 percent) of satellite C-band, while using a 20-megahertz guard band to protect nearby satellite signals from interference. That Spengler led a sea change in industry thinking that united the world’s biggest satellite operators on a highly controversial topic is clear as day, however.

That leadership has catapulted Intelsat’s stock from $3.64 on Jan. 2 to over $37 a share this October. The C-band plan aligns with important pillars of the U.S. Federal Communication Commission’s proposed rulemaking, which positions it well to be the agency’s go-forward strategy when it decides how to reallocate C-band in 2019.

Though it is early days, the success of the Intelsat-led plan has the potential to generate cash flows that can drastically reduce the company’s weighty $14.3 billion debt load. As a highly leveraged company, Intelsat has admitted it is not able to make industry-leading moves the way it would like. The C-Band Alliance, however, is one such move.

LAUNCH SERVICE AGREEMENTS

Readers’ Choice

- Lockheed Martin wins $7.2 billion GPS 3 contract

Other Finalists

- Northrop Grumman acquires Orbital ATK

- Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport signs Rocket Lab as tenant

In a year of major investments and acquisitions, the most influential deal of the year involved a set of awards by the Air Force that sets the stage for a potential realignment of the U.S. launch industry.

The Launch Service Agreement (LSA) contracts awarded by the U.S. Air Force in October to Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems and United Launch Alliance are intended to support the development of a new generation of launch systems, providing improved access to space and ending reliance on the Atlas 5 and its Russian main engine.

For two of the companies, the LSA awards were likely make-or-break. It’s unlikely that United Launch Alliance would have been able to continue the Vulcan Centaur without the financial support in the form of nearly $1 billion from the Air Force. Northrop Grumman would have almost certainly dropped plans to develop OmegA had it not secured an LSA award valued at nearly $800 million.

It’s a different story for Blue Origin, though: the company, backed by Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos, would have continued development of its New Glenn rocket regardless of any Air Force funding. However, the $500 million it received will go toward specific capabilities, including a launch site at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, needed to be able to support national security space missions but which it might otherwise not have developed.

The LSA awards are also a major deal because of who didn’t win: SpaceX. While the company was widely considered a front-runner for an award, it came away empty-handed. SpaceX presumably sought LSA funds to help finance its next-generation launch system, until recently called Big Falcon Rocket (BFR). The Air Force may not have seen value from investing in BFR, even as it relies on SpaceX’s existing rockets.

The LSA awards mirrors the Air Force’s last major effort to develop new launch vehicles. Like the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle program, the LSA program expects companies to invest their own money alongside Air Force funds to develop those vehicles. The EELV program was a technical success but a business failure, as the commercial markets expected in the late 1990s to be able to support two vehicles didn’t materialize. This time both the Air Force and industry hope the market is different. But even if it is, not all competitors are guaranteed to succeed. The Air Force plans to select only two companies for phase 2 of the LSA program, a future “block buy” of launch services. SpaceX, despite not winning an LSA award, will be eligible for this competition, a high-stakes race that will shape the future of the American launch industry.

TOM MUELLER

Readers’ Choice

- Tom Mueller, SpaceX

Other Finalists

- Steve Volz, NOAA

- Dan Rasky, NASA

- Delta 2 rocket

- Space Angels

Every word uttered by Elon Musk makes headlines around the world. Far less attention focuses on SpaceX’s propulsion chief technology officer, Thomas Mueller. Without Mueller’s expertise, though, it’s hard to imagine SpaceX succeeding in slashing the cost of space access or producing reliable, reusable rockets.

Mueller, who worked his way through college as a logger, holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mechanical engineering. Before helping start SpaceX as one of Musk’s original hires, he spent 14 years at TRW, an American corporation known for automotive parts as well as satellites, space-based observatories and rocket engines. Long before TRW sold its space business to Northrop Grumman in 2002, the company produced the Lunar Module Descent Engine for the Apollo program, the first engine for human spaceflight that could be throttled. At TRW, Mueller carried forward the throttling concept, with TR-106, a powerful, throttleable booster engine fueled by liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen.

Not content to leave work at the office, Mueller was building a 36-kilogram rocket engine in his garage when Musk invited him to help found Space Exploration Technologies in 2002.

Sixteen years later, Mueller remains at the Hawthorne, California, company where he developed engines for the Falcon and Dragon spacecraft. Mueller-led teams invented the Merlin 1A and Kestrel 4 engines for Falcon 1, the first privately operated liquid rocket to reach orbit. Then, they turned their attention to Falcon 9’s Merlin 1C, 1D and Vacuum engines, the keys to the booster’s reusability.

In recent years, Mueller has devoted his attention to Raptor, a family of reusable liquid oxygen, liquid methane staged-combustion engines for the booster and upper stage of Starship, the launch vehicle SpaceX is building for interplanetary transportation.

“That rocket is going to be the real game-changer,” Mueller told New York University’s Astronomy Club in 2017 via Skype. “I would say that the Falcon 9 is evolutionary; a reusable rocket that greatly reduces the cost of access to space…We want a hundred or more reduction in costs. That’s what the Mars rocket’s going to do.”

In the early 2000s, it was popular to dismiss bold predictions from SpaceX. With 18 launches in 2017 and 18 more completed in the first 11 months of 2018, including the first flight of the Falcon Heavy, claims by the company’s propulsion chief are harder to discount.